Does the Online News Act make any sense?

The Canadian law regulating the relationship between platforms and news outlets already has big consequences

Last week, Google announced they’ll be cutting off all Canadian news from its platform, including search and Google News, following the implementation of the Online News Act.

That followed Meta announcing it would do the same thing on its platforms. It’s already started to hide news outlets on Instagram.

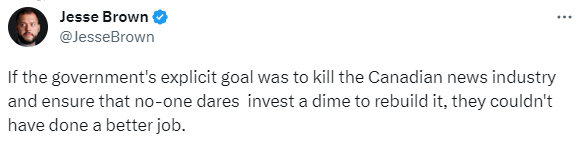

And while the response the Meta ban was somewhat tepid, the reaction to the Google news from certain media industry members was instant.

Losing both search and social amounts to something like 40 to 60 per cent of all traffic evaporating into the air. In an ad-based business, losing that many eyeballs is well, bad.

Google and Meta are both ending existing deals they had with news outlets. That includes an arrangement with the Canadian Press wire service that created 30 fellowship positions over two and half years.

So given the immediate cost, is the Online News Act worth it? Does it even make sense?

What is the Online News Act exactly?

The Online News Act (ONA) is, in its most basic form, a law that requires online platforms to make deals with news publishers, in exchange for the right to display or preview content created by those publishers.1

Basically, if CTV News publishes a web story that appears on Google or Facebook or Twitter, in any form, CTV News is owed some kind of fee. The fee is to be negotiated between the platform and the publisher, and if they can’t work out an arrangement, it goes to a government arbiter.

The ONA is heavily inspired by the Australian News Media Bargaining Code, which works to achieve the same goal. And according to the the Australian government it did its job — the law generated more than $177 million for the news industry.

Andrew Dodd, director of the Centre for Advancing Journalism at the University of Melbourne, called it “not a panacea but it has definitely pumped new life into the news media.”

“Advertisements for mostly entry-level journalism positions are springing up and media companies are clearly investing in their newsrooms again,” said Dodd.

When the law was about to go into effect in 2021, Meta briefly backed out of the Australian market, even hiding Australian government pages. But after an eleventh hour negotiations, it ultimately relented.

Why? Well, the Australian law to works in a tricky way. The bargaining code requires the government to designate which corporations must make negotiations with news outlets. And in the end, the government didn’t designate anyone.

That left the law an implicit but not active threat that if Google and Meta didn’t make negotiations independently, they would be beholden to government rules. But it also let them to pick and choose which outlets they partnered with, and on what terms.

This strategic ambiguity is partly what brought Meta back into the fold.

“The big tech companies know regulation has to come eventually. They want the model that gives them legitimacy and certainty,” said Dodd.

“But they also want the least onerous oversight and the cheapest model they can find.”

The Canadian model tries to fix that gap in legislation. The ONA doesn’t leave it to politicians to decide who counts as a news organization, who counts as a large platform, or what counts as an appropriate deal. That will be up to the CRTC, an independent government agency.

From a transparency standpoint, that’s a potential improvement.

But it also forces platforms to submit to the logic of the law — which is they have to pay news organizations for links. In Australia, Google and Meta were allowed to bypass the specifics of the law in favour of the broad idea of “deals” and “news.”

In Canada, they won’t be able to.

"I wish there was a way to reach deals or come to some kind of compromised solution outside the framework of Bill C-18," Rachel Curran, Meta’s head of public policy in Canada, told CBC News.

"But there's really not."

So the next obvious question is: Should the platforms compensate news organizations for links?

The relationship between publishers and platforms

The government and media lobbyists argue that:

Google and Meta make a lot of fucking money — which is true. Alphabet, which owns Google, made $76 billion US in profits alone last year. Meta had $116.6 billion US in revenue, with a 20 per cent profit margin.

These platforms have built their value on the backs of publishers — that the reason people go on Google Dot Com is to search “tornado alberta”2 and get this Global News result.

That’s Dodd’s argument as well — the fact that Google and Meta made deals in Australia is a concession that they need news on their platform.

But it’s hard to tell how valuable news is to these platforms. Meta has been pushing news out of Facebook’s news feed for years and it’s said news represents only 3 per cent of all content.

Google meanwhile argues that they function more like a newsstand that displays all the outlets for people to access. They also object to the law’s key mechanism, a price on content and links.

"The unprecedented decision to put a price on links (a so-called 'link tax') creates uncertainty for our products and exposes us to uncapped financial liability simply for facilitating Canadians' access to news from Canadian publishers,” wrote Alphabet’s president of global affairs, Kent Walker.

I think it’s fair to say if it cost money for anyone link to any website that would be bad. Casey Newton of Platformer makes the case that this would fundamentally break the internet.

But that hypothetical isn’t really what the law does. It does have a broad range of companies that could be considered news outlets, but not an infinite list. The CRTC will make the final determination.

That’s the issue though. The ONA marks in law that the news organizations provide the value, not the platforms. But in order for the platforms to not be hit by legislation by every country on the planet, they have to argue the opposite. It’s the news orgs who exist because of them.

And they’re not entirely wrong.

A Press Gazette report noted that for 546 UK and US sites, search hovers around 35 per cent of all traffic to news articles, while social is down to 28 per cent. These numbers will differ from site to site and from story to story. But simple math will tell you that’s more than half of all traffic.

Most online news outlets are ad-supported, with a small base of subscribers, if any. And the ad-market hasn’t looked great the last few years/decade/my lifetime. Sixty four news outlets closed in the last two years. Everyone needs all the traffic they can get.

And while the news industry collapsing might justify government support, it doesn’t necessarily justify the ONA.

Diana Bossio, a news media researcher at the Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, argues that neither the Canadian or Australian laws are sustainable long term.

“It's hinging legislation on the fortunes of private companies, and their willingness to negotiate. Instead we've seen platforms just walk away from news content altogether,” she said.

Her belief is that if the problem is news doesn’t make a lot of money from advertising, why not target Google’s advertising monopoly?3 A UK study showed ad tech companies, like Google, make 42 cents US on every dollar spent on online advertising, leaving the publisher with 51 cents.

Cory Doctorow, a Canadian journalist, activist and author, believes that the ONA is a huge missed opportunity in that regard.

A major critique of the Australian law was that it benefited larger news outlets, like News Corp or the public broadcaster ABC much more than it did a smaller outlets. The Conversation Australia said they only received enough money to hire one more person. A similar situation will likely happen in Canada, with the bulk of the money going to the CBC and Rogers Sports & Media — not newspapers.

An ad-market solution could benefit news outlets more evenly and last longer.

“We should really want there to be a regime in which small news outlets and new news outlets that enter the field have as much of a benefit, if not more, as these giant dominant news outlets,” said Doctorow.

Is the Online News Act fallout fixable?

That depends what you mean by fixable.

Can the legislation be amended or changed? It’s already passed into law.

Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez is being supported by both the New Democratic Party and the Bloc Québécois4 — a rare moment of political unity. Even Quebec’s premier, Francois Legault, is in favour of the law.

"We're going to keep standing our ground. After all, if the government can't stand up for Canadians against tech giants, who will?" Rodriguez told CBC News.5

He has the prime minister’s full support too, who told the CBC this is a “dispute over democracy.”

So there’s no signs just yet of the government making changes, or presenting new directives on how the law should be implemented.

Will Meta and Google come back to the table? It’s unclear. While Meta came back to the table in Australia, that was before the legislation passed.

“It's a different context. Meta is not in the same financial position it was, and the news block is happening now that the legislation is a done deal,” said Bossio.

“I don't know that the Canadian government has any bargaining chips left to deal with both platforms turning away from Canadian news.”

Rodriguez told CBC News they’re still talking to Google. But it’s worth noting Spain went eight years without being listed in Google News over a similar law, so this stand-off may last a while.

Will the Canadian media industry find a way out? It’s hard to say how the news block will impact Canadian news. It will likely hit smaller, newer outlets much harder than bigger, established ones, the latter of whom can count on an audience that regularly visits their home page.

In Australia, ABC News saw downloads of their app shoot up, and in Spain, the News Media Alliance (a U.S. news trade association) says the traffic hit wasn’t as big as people expected. Though Spain was removed only from Google’s News product and not search entirely.

Dodd, having seen Australia’s industry grow, believes that a future disconnected from search and social is survivable.

“There would be mass fear and inevitably some casualties, but after all the upheaval of digital disruption [in the 2000s] the media became more adaptable and resourceful,” he said.

“Such an aftershock would also prompt innovation which would lead to competition for the tech companies, which are now becoming the ones with the most to lose.”

If I do this right, I’ll never have to explain the ONA again…

There’s also a shocking number of people who just search Facebook or Global News because they’ve never thought to bookmark their favourite websites. Does Google serve those websites, or do those websites provide Google with easy money?

Although maybe soon joined by Amazon and Apple?

It never hurts politically to have Pierre Karl Péladeau on same page as you (unless you’re the PQs in 2015). Quebecor, PKP’s French news giant, just announced they’re pulling all advertising on Facebook and Instagram.

Look, I’m trying not to just summarize this CBC News article. It’s interesting! Read it!